Reason and the Faustian Bargain

Progress: it is very hard to stay on the path.

Using reason to solve problems is nothing new, nor is its application in governance. What transformed Europe in the second millennium was the emergence of a social movement dedicated to applying reason to the discovery of truth rather than the preservation of authority. From this movement grew democracy, progress, and the modern public sphere—the public’s influence over governance and its protection against an oppressive state.

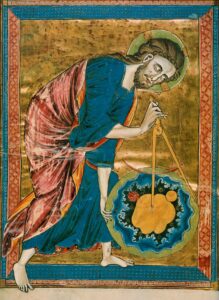

They say that God is truth and the Devil the prince of lies. Truth leads to God; lies lead to the Devil. Follow truth and you are led to God. Yet Christians long held that it was sinful to pry into and exploit God’s secrets, oppose His will, or usurp His powers. Despite warnings, from the era of the historical Johann Faust onward, this restriction gradually weakened. The premise of reason was that everything could be understood, that God does not intervene. Within that premise, God becomes irrelevant

It is common in the West to interpret the final book of the New Testament of the Bible, The Book of Revelation, as a prophetic completion of a Christian trajectory of humanity’s destiny—from original sin to an end-of-the-world battle between God and Satan and final judgment of all humans leading to damnation or salvation. It is easy to see progress as moving toward that apocalypse or toward salvation, possibly in the form of a utopia on Earth and our own saving transcendence.

Like Faust, our efforts to make a better life tempts us to make deals with the Devil that may lead to damnation. The story of Faust becomes a metaphor for the trajectory of Western civilization, and it fits within a Christian narrative.

II. The Nature and Power of Reason

A. What Reason Is

Reason is the process of working step by step toward a conclusion, with each step justified by evidence or logical probability. It is internally coherent, demonstrable and defensible, reproducible, and effective. It is a method, a social force, and a moral authority.

Unlike instinct, emotion, habit, tradition, magical thinking, or faith—all of which may be forms of conditioned behaviour—formal reasoning is a deliberate act, or so it seems.

Our capacity to reason deliberately has long been an argument for free will. Yet feeling that we possess free will does not prove that we do. Reasoning effectively does not come naturally; it must be taught, as must the art of gathering and assessing information. We learn to apply reason within disciplines such as science, engineering, law, and philosophy.

Effective reasoning requires rules of intellectual hygiene: seek truth, accept evidence, reject claims that cannot be supported, remain sceptical, and tolerate uncomfortable conclusions.

B. The Promise and Peril of Reason

Most of us hesitate to make reason a guiding principle or to face its implications. Reason challenges faith and tradition and presumes to govern them. It leads to change—often unwelcome—and can be used to rationalize evil. It is dangerous. When reason dismantles faith, tradition, and instinct, it risks undoing society itself.

One unpleasant truth is that reason does not require God. In fact, it works best when the premise is that all things can be understood and predicted. It is the foundation of modern science. In the scientific method there is no room for what cannot be proved—no place for divine intervention.

When reason is applied with inadequate information or judgement, the results can be disastrous. As in the story of Faust, who aspired to powers beyond his control, reason misused can lead to terrible outcomes:

“He calls it Reason, but only uses it

To be more a beast than any beast as yet.”

— Goethe, *Faust I*, “Prologue in Heaven”

Reason itself is neutral—a tool for discovering truth by building on truth. It works as well for calculating how much wood is needed to build a deck as for uncovering the laws of nature.

But we live in groups, and reason achieves far greater things collectively than individually, and the largest group that can work together to use reason is the general public. But that requires certain conditions: trained, educated, capable and well-intentioned participants, access to reliable information, and norms of civility, openness, cooperation, and goodwill.

Reason convinces. Using it, the public can advance common interests and counter the dominance of Church and State. It is the people’s most effective defence, the foundation of democratic progress. But without those conditions, there is no public voice and no power. Then, under pressure, there is either obedience or revolution.

III. Reason and Christianity

A. The Traditional Tension

Christians believe that humans were created in the image of God and that reason is part of that divine image. The capacity for reason, expressed through free will, distinguishes humanity from other animals.

In this view, God created the universe to operate according to natural laws that could be understood through reason. Because God is truth, and reason leads to truth, the pursuit of knowledge brings humanity closer to God.

Still, reason was of limited interest to devout Europeans; it seemed confined to the material world, which belonged to God—or the Devil. Salvation through faith was more important.

It was long held that life unfolded according to God’s plan and that it was sinful to interfere with it or to uncover forbidden secrets—as Faust attempted. From Faust’s fifteenth century through to modern secular society, we see a progressive erosion of that taboo.

The Bible demands faith, yet reason finds faith unreasonable. That’s okay because faith is beyond reason. Thus, many have practised both piety and reason, each in its proper sphere.

B. Historical Challenges

Reason has also humbled humanity. Observation of the heavens, based on ancient Babylonian records and refined by Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, showed that Earth is not the centre of the universe—possibly not even the centre of God’s. That was a hard blow for Christians, losing the comfort of being in God’s hands, realizing an insignificance which has only grown as succeeding centuries have shown the vastness of the Universe.1

It remained heretical to dissuade others from faith and salvation, and dangerous to suggest the Bible was wrong. Discoveries such as Copernicus’s heliocentrism caused deep anxiety about reason’s potential to undermine faith.

Certainly, reason doesn’t always go our way or maybe even God’s. Thanks to reason we now find the appearance of reasoning ability in great apes, dolphins, elephants, crows and ravens, parrots, octopuses, dogs, pigs, rats, and bees, among others, including AI, any of which could be forgiven for assuming that they were created in the image of God, had free will, and were uniquely suited to determine the destiny of the planet Earth and all known forms of life.

IV. Reason as a Social Force: Institutions and the Public Sphere

A. Preconditions for a Rational Society

Reason’s rise as a social force depended on several conditions: growing literacy, prosperity, and institutions devoted to learning—universities, libraries, and scientific societies. Innovations like the printing press (c. 1440) and new social spaces, such as coffee houses, allowed ideas to circulate freely. These developments laid the groundwork for what later became known as the Age of Reason.

This movement remains embodied in universities, learned societies, and the press—institutions dedicated, at least in principle, to the discovery and dissemination of truth.

B. Resistance from Authority

Yet from the beginning, they have faced resistance from Church, State, and private powers that seek to control or suppress knowledge.

The segment of intellectual life that shapes governance is called the public sphere, separate from both Church and State. When it is corrupted or captured, and rational discourse is undermined, citizens lose influence.

V. The Faust Legend as Mirror of Western Transformation

A. Historical Evolution of the Story

While historians often locate the Age of Reason in the 17th and 18th centuries, its roots extend back to the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution. The Faust legend mirrors this transformation—from medieval religious anxieties to the humanist ambitions of the Enlightenment.

The historical Johann Faust, active in early 16th-century Germany, was a scholar and itinerant alchemist. Around 1587, an anonymous Lutheran compiled Historia von D. Johann Fausten (the Faustbuch), a cautionary tale against hubris and forbidden knowledge. English translation followed in 1588, and soon after, Marlowe dramatized it in Doctor Faustus (~1592).

Two centuries later, Goethe reshaped the legend into a philosophical epic (1808–1832). From chapbook (literally, cheap book) to high art, the Faust myth charts the rise of Europe’s educated public and changing attitudes toward knowledge and faith.

B. Why Faust Matters

From the 15th century of the original Faust through to the death of Goethe in 1832 and beyond, the culture of reason grew with high ideals, driven by exciting new discoveries and the realization that we had the opportunity to both create a better life in the material world and to come closer to God.

Social conditions roughly improved alongside the Faust legend in the 15th century. The legend’s popularity and successive versions reflect evolving cultural anxieties—about ambition, worldly knowledge, the erosion of faith, salvation, and Europe’s growing temptation to steal and misuse God’s forbidden knowledge and power.

Originating in a Lutheran context, Faust serves as a caution against hubris, ambition, materialism, and the theft of divine prerogatives—and Europe was on its way to do precisely that.

Truth is dangerous in the wrong hands. Reason has given us immense power, which we use in pursuit of an earthly paradise. But it is a precarious path. Humanity has conjured forces it cannot control. Our technological civilization, built on reason, risks destroying the natural and moral order it depends upon, and we gamble that the harm we cause today can be repaired tomorrow.

The Faust story serves as a metaphor for Western civilization: a wager that progress will redeem its own transgressions. From a Christian perspective, it is a Faustian bargain—the exchange of the soul for worldly power. It is easy to imagine the hand of Mephistopheles in it and our looming damnation.

We don’t know if the Devil’s in it. Given the traditional Christian attitude to life on earth, from that perspective, yes. The Devil creates illusion. The Devil answers our quest for better life in this material world with distractions and diversions as we forget about God and pursue our selfish impulses. It is hard to stay on the path.

VI. The Public Sphere in Crisis—The Degradation of the Public Sphere

A. From Rational Discourse to Manipulated Perception

By Goethe’s time (1749–1832), the Age of Reason was in full bloom. Salons and learned societies offered spaces for civil, reasoned debate. Ideals like “liberty, equality, and fraternity” emerged from this culture, reshaping European politics. The public sphere—rational, discursive, and collective—became a foundation of modern democracy.

Today, communication is global, instantaneous, and overwhelming. Yet the public sphere is once again endangered—this time by distortion, distraction, and manipulation.

It isn’t necessarily deliberate or intentional, but the Devil’s realm is illusion. In our age of managed perceptions and synthetic experiences, we risk detaching entirely from reality, choosing magical thinking over reality.

B. The State’s Growing Reach

In the West, the Church has lost much authority—a casualty of reason, democracy, and the Faustian promise of progress. Yet dogmatic nationalism and anti-rational populism now threaten to occupy that vacuum.

And while some may rationalize that aligning with evil to serve divine ends (echoing Judas’ betrayal of Christ) helps fulfill their interpretation of God’s plan, that’s a very Faustian thing to do, and is what the morality tale warns against.

As Alexis de Tocqueville observed:

“No sovereign ever lived in former ages so absolute or so powerful as to undertake to administer by his own agency, and without the assistance of intermediate powers, all the parts of a great empire; none ever attempted to subject all his subjects indiscriminately to strict uniformity of regulation and personally to tutor and direct every member of the community. The notion of such an undertaking never occurred to the human mind…”

— Democracy In America — Volume 2 by Tocqueville, Alexis de, 1805-1859, vol. 2, ch. 4.

The state remains a threat, and it grows. In the nineteenth century de Tocqueville thought democracy was still safe from the state’s reach. That is no longer true. The management of public sentiment has become central to power—and, when corrupted, to oppression.

The attack on truth coincides with a massive increase in the flow of information and the means to create a fantasy world, much like the War on Terrorism coincided with that same flow of information and the means for mass surveillance. De Tocqueville noted over a hundred years ago that one thing protecting citizens from total authoritarianism is the state’s lack of reach, but that barrier has been surpassed.

C. Symbols, Illusion, and the Loss of Truth

Civilization itself is built on symbols—laws, money, maps, words—all representations that stand in for a truth. In Goethe’s Faust II, paper money symbolizes this dangerous abstraction: wealth conjured from nothing. What we now accept as credit.

Representations can be necessary symbolic abstractions and they can be dangerous symbolic substitutions.

We must always bear in mind what the symbols represent. When symbols lose their grounding, they become idols. In the United States of America, the Pledge of Allegiance says “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” But people revere the flag without remembering that for which it stands, and when someone wraps themselves in the flag, people are led astray. In such confusion, truth yields to emotion, and reason falters.

“The Chancellor Satan lays out his gilded nets, for you,

These things don’t square with what’s good and true.”

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1749–1832) – Faust, Part II: Act I Scenes I to VII. https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/German/FaustIIActIScenesItoVII.php#Act_I_Scene_II. Accessed 8 Nov. 2025.

For those who want to control the public sphere compliance is not required. Controlling the public sphere no longer requires force: distraction, division. ignorance, and apathy make citizens easier to manipulate.

VII. The Faustian Age

“We are sometimes afraid of the truth… and yet we must not be afraid of the truth because it alone is beautiful.”

— Henri Poincaré, La valeur de la science (1911)2

We are in the midst of a vast experiment—faith not in God, but in ourselves: faith that reason alone can solve the problems it creates. We are better off, but not necessarily better. Reason is not wisdom, nor is it compassion.

Created in the image of God, we are representations of God. If you don’t believe in God or the Devil, substitute ourselves. Perception is representation, too. Our mind is the master of representation. The reality we experience is its representation. It interprets the world and gives it flavour and feel, it explains it to us, but it can be manipulated.

At best we have limited free will. Do we really need the Devil’s help? Reason suggests we’re just animals, with little real control over our actions, individually or collectively. All this hand-wringing may be for nothing.

Isn’t that a Faustian ending? Stripped of divinity and revealed as automatons—soulless, neither damned nor divine.

- The Earth moved. Copernicus was a Catholic canon who delayed publication of his great work (showing the earth and the other planets orbiting the sun and not the other way around) until his death, partly in case the Church didn’t approve. While the Church appreciated reason, they guarded against error affecting faith. [↩]

- “However, sometimes the truth frightens us. And indeed, we know that it is sometimes disappointing, that it is a phantom that appears to us only for a moment before constantly fleeing, that we must pursue it further and further, without ever being able to reach it. And yet, to act, one must stop, αναγκη στηναι, as some Greek—Aristotle or someone else—said. We also know how often it is cruel, and we wonder if illusion is not not only more comforting but also more strengthening; for it is illusion that gives us confidence. When it has disappeared, will hope remain, and will we have the courage to act? It is like a horse harnessed to a carousel that would certainly refuse to move forward if one did not take the precaution of blindfolding it. And then, to seek the truth, one must be independent, completely independent. If we want to act, on the contrary, if we want to be strong, we must be united. That is why many of us are afraid of the truth; we see it as a source of weakness. And yet we must not be afraid of the truth because it alone is beautiful.” — Poincaré, Henri, 1854-1912. La valeur de la science, par H. Poincare. Paris : e. Flammarion, 1911 https://archive.org/details/valeurdelascience00poin/page/n9/mode/2up. Trans. Google Translate. Dec 8, 2025 [↩]